Museo de América

| |

Façade of the museum | |

| |

| Established | 1941 |

|---|---|

| Location | Madrid, Spain |

| Type | Artistic, archaeological and ethnographic |

| Owner | General State Administration |

| Public transit access |

|

| Website | museodeamerica |

| Official name | Museo de América |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 1962 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0001378 |

The Museo de América (English: Museum of America) is a Spanish national museum of arts, archaeology and ethnography in Madrid. Its collections cover the whole of the Americas and range from the Paleolithic period to the present day.

The museum was established by the Spanish State and its initial pieces came from the former collection of American archaeological and ethnographic artifacts from the National Archaeological Museum, Madrid and the Prado Museum, as well as exhibiting a number of unrelated donations, deposits and purchases.[1] It has a major collection of 18th c. casta paintings, one by Miguel Cabrera, who created a set of 16 large format casta paintings. The museum's most famous painting is by Mexican artist, Luis de Mena, of the Virgin of Guadalupe and castas on a single canvas.[2]

History

The institution was founded by a decree of 19 April 1941 and opened in 1944 inside the building housing the National Archaeological Museum.[3] After all the initial holdings were moved to a newly built premises in the Ciudad Universitaria, the building was inaugurated on 12 October 1965.[4] After a series of renovations of the building, which was previously shared with a number of unrelated institutions, the museum was reopened on 12 October 1994, this time exclusively occupying the entire building.[5] As part of preparation for the re-opening, a collecting programme was established, with artifacts from Spain's first Caribbean settlement on Hispaniola (modern Haiti and the Dominican Republic) found by anthropologist Soraya Aracena.[6]

Collection

The permanent exhibit is divided into five major thematic areas:

- An awareness of the Americas

- The reality of the Americas

- Society

- Religion

- Communication

-

Ceramic vessel representing a crustacean. Moche culture artwork from Peru.

Ceramic vessel representing a crustacean. Moche culture artwork from Peru. -

Bronze helmet of a 16th-century Spanish soldier.

Bronze helmet of a 16th-century Spanish soldier. -

Chimú vessel showing a sexual act between men.

Chimú vessel showing a sexual act between men. -

![Helmet and collar made by the Tlingit people (late 18th century).[7]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Casco_y_collera_de_lobo_tlingit_%28M._Am%C3%A9rica%2C_Madrid%29_02.jpg/152px-Casco_y_collera_de_lobo_tlingit_%28M._Am%C3%A9rica%2C_Madrid%29_02.jpg) Helmet and collar made by the Tlingit people (late 18th century).[7]

Helmet and collar made by the Tlingit people (late 18th century).[7] -

![Statuette of a Quimbaya cacique [es] (200–1000 AD)[8]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica_Quimbaya_treasure_02.jpg/124px-Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica_Quimbaya_treasure_02.jpg) Statuette of a Quimbaya cacique [es] (200–1000 AD)[8]

Statuette of a Quimbaya cacique [es] (200–1000 AD)[8] -

![View of Seville, attributed to Alonso Sánchez Coello (late 16th century)[9]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/La_sevilla_del_sigloXVI.jpg/377px-La_sevilla_del_sigloXVI.jpg) View of Seville, attributed to Alonso Sánchez Coello (late 16th century)[9]

View of Seville, attributed to Alonso Sánchez Coello (late 16th century)[9] -

![Maya Stele of Madrid [es] (600–900 AD)[10]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Estela_%2847702715951%29.jpg/140px-Estela_%2847702715951%29.jpg) Maya Stele of Madrid [es] (600–900 AD)[10]

Maya Stele of Madrid [es] (600–900 AD)[10] -

![Nazca pot (1–600 AD)[11]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Vasija_que_representa_a_un_pescador_tocando_la_flauta._Cultura_Nazca_%28100_a._C.-700_d._C.%29._Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica.jpg/229px-Vasija_que_representa_a_un_pescador_tocando_la_flauta._Cultura_Nazca_%28100_a._C.-700_d._C.%29._Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica.jpg) Nazca pot (1–600 AD)[11]

Nazca pot (1–600 AD)[11] - Aztec Codex Tudela

-

![Luis de Mena, Casta painting with the Virgin of Guadalupe, 1750[12]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Casta_Painting_by_Luis_de_Mena.jpg/153px-Casta_Painting_by_Luis_de_Mena.jpg) Luis de Mena, Casta painting with the Virgin of Guadalupe, 1750[12]

Luis de Mena, Casta painting with the Virgin of Guadalupe, 1750[12] -

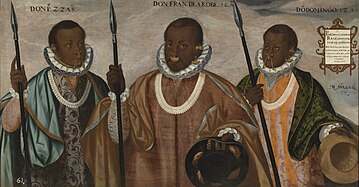

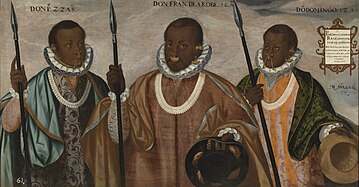

The Mulattos of Esmeraldas, by Andrés Sánchez Gallque (Quito School), 1599 (depósito del Museo del Prado).

The Mulattos of Esmeraldas, by Andrés Sánchez Gallque (Quito School), 1599 (depósito del Museo del Prado). -

Conquest of Mexico. Reception of Moctezuma by Mexicans in canoes, enconchado painting Juan y Miguel González, Mexican School, 1698 (depósito del Prado).

Conquest of Mexico. Reception of Moctezuma by Mexicans in canoes, enconchado painting Juan y Miguel González, Mexican School, 1698 (depósito del Prado). -

Escena de mestizaje (Casta painting): De chino cambujo e india, loba. Miguel Cabrera, Mexican School, 1763.

Escena de mestizaje (Casta painting): De chino cambujo e india, loba. Miguel Cabrera, Mexican School, 1763. -

Yapanga of Quito with the dress that this class of women wore to please. Lienzo de Vicente Albán de 1783, Quito School.

Yapanga of Quito with the dress that this class of women wore to please. Lienzo de Vicente Albán de 1783, Quito School.

See also

- Museo Nacional de Antropología (Madrid), also featuring American pieces

References

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Sarah Cline, “Guadalupe and the Castas: The Power of a Singular Colonial Mexican Painting.” Mexican Studies/Esudios Mexicanos Vol. 31, Issue 2, Summer 2015, pages 218-46.;Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2005). Colonial Art in Latin America. New York: PhaidonPress. pp. 66–68.;Bleichmar, Daniela (2012), Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 173;Deans-Smith, Susan (Winter 2005). "Creating the Colonial Subject: Casta Paintings, Collectors, and Critics in Eighteenth-Century Mexico and Spain". Colonial Latin American Review: 169–204.; Elena Isabel Estrada de Gerlero,"The Representation of ‘Heathen Indians’ in Mexican Casta Painting." In New World Orders, edited by Ilona Katzew. NY: Americas Society, 1996, 50.; María Concepción García Sáiz. Las castas mexicanas: un género pictórico americano. Milan: Olivetti, 1989, set III; 66–67; Ilona Katzew, Casta Paintings: Images of Race in Eighteenth-CenturyMexico. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004, 194–195; María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008, dust cover; 257; Cruz Martínez de la Torre and María Paz Cabello Caro. Museo de América, exhibition catalogue. Madrid: IberCaja/Marot, 1997, 130; Jeanette Favrot Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe: From Black Madonna to Queen of the Americas. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014, 256–257; Nina M. Scott, "Measuring Ingredients: Food and Domesticity in Mexican Casta Paintings." Gastronomica 5, no. 11 (2005): 70–79.

- ^ Krizmanics 2018, p. 40.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 89.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 90.

- ^ "Calendario-Conversatorio-RD – Jornada Centenaria Ricardo E. Alegría Gallardo". centenarioricardoalegria.com. Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 99.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 95.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 112.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 91.

- ^ "Vasija Nazca". Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte.

- ^ Sarah Cline, “Guadalupe and the Castas: The Power of a Singular Colonial Mexican Painting.” Mexican Studies/Esudios Mexicanos Vol. 31, Issue 2, Summer 2015, pages 218-46.

- García Sáiz, Mª Concepción; Jiménez Villalba, Félix (2009). "Museo de América, mucho más que un museo" (PDF). Artigrama. 24 (24). Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza: 83–118. doi:10.26754/ojs_artigrama/artigrama.2009247698. ISSN 0213-1498. S2CID 257308144.

- Krizmanics, Georg T. A. (2018). "El Museo de América de Madrid: ¿un instrumento para la política exterior española?". A Contracorriente. 15 (2): 39–61.

External links

- Northwest Coast art in the Museo de América

- Official website

- v

- t

- e

- Prado National Museum (Madrid)

- Queen Sofía Art Center National Museum (Madrid)

- Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum (Madrid)

- National Museum and Research Center of Altamira (Santillana del Mar)

- Museum of the Americas (Madrid)

- National Museum of Anthropology (Madrid)

- National Archaeological Museum (Madrid)

- National Museum of Subaquatic Archaeology (Cartagena)

- The House of Architecture (Madrid)

- González Martí National Museum of Ceramics and Decorative Arts (Valencia)

- Cerralbo Museum (Madrid)

- Cervantes' House Museum (Valladolid)

- Museum of Garment - Ethnologic Heritage Research Center (Madrid)

- National Museum of Decorative Arts (Madrid)

- El Greco Museum (Toledo)

- Lázaro Galdiano Museum (Madrid)

- National Museum of Roman Art (Mérida)

- National Museum of Romanticism (Madrid)

- National Museum of Sculpture (Valladolid)

- Sephardic Museum (Toledo)

- Sorolla Museum (Madrid)

- National Museum of Theatre (Almagro)

- Museum of the Army (Toledo)

- Naval Museum (Madrid)

- Museum of Aeronautics and Astronautics (Madrid)

technology

- Royal Botanical Garden (Madrid)

- Geomineral Museum (Madrid)

- Museum of the Royal Mint (Madrid)

- National Museum of Natural Sciences (Madrid)

- Railway Museum (Madrid)

- Railway Museum of Catalonia (Vilanova i la Geltrú)

- National Museum of Science and Technology (La Coruña and Alcobendas)

40°26′18″N 3°43′19″W / 40.4383°N 3.7220°W / 40.4383; -3.7220

| This article about a museum in Spain or its islands is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

- v

- t

- e

![Helmet and collar made by the Tlingit people (late 18th century).[7]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Casco_y_collera_de_lobo_tlingit_%28M._Am%C3%A9rica%2C_Madrid%29_02.jpg/152px-Casco_y_collera_de_lobo_tlingit_%28M._Am%C3%A9rica%2C_Madrid%29_02.jpg)

![Statuette of a Quimbaya cacique [es] (200–1000 AD)[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica_Quimbaya_treasure_02.jpg/124px-Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica_Quimbaya_treasure_02.jpg)

![View of Seville, attributed to Alonso Sánchez Coello (late 16th century)[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/La_sevilla_del_sigloXVI.jpg/377px-La_sevilla_del_sigloXVI.jpg)

![Maya Stele of Madrid [es] (600–900 AD)[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Estela_%2847702715951%29.jpg/140px-Estela_%2847702715951%29.jpg)

![Nazca pot (1–600 AD)[11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Vasija_que_representa_a_un_pescador_tocando_la_flauta._Cultura_Nazca_%28100_a._C.-700_d._C.%29._Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica.jpg/229px-Vasija_que_representa_a_un_pescador_tocando_la_flauta._Cultura_Nazca_%28100_a._C.-700_d._C.%29._Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica.jpg)

![Luis de Mena, Casta painting with the Virgin of Guadalupe, 1750[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Casta_Painting_by_Luis_de_Mena.jpg/153px-Casta_Painting_by_Luis_de_Mena.jpg)