MANIAC I

The MANIAC I (Mathematical Analyzer Numerical Integrator and Automatic Computer Model I)[1][2] was an early computer built under the direction of Nicholas Metropolis at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. It was based on the von Neumann architecture of the IAS, developed by John von Neumann. As with almost all computers of its era, it was a one-of-a-kind machine that could not exchange programs with other computers (even the several other machines based on the IAS). Metropolis chose the name MANIAC in the hope of stopping the rash of silly acronyms for machine names,[3] although von Neumann may have suggested the name to him.

The MANIAC weighed about 1,000 pounds (0.50 short tons; 0.45 t).[4][5]

The first task assigned to the Los Alamos Maniac was to perform more precise and extensive calculations of the thermonuclear process.[6] In 1953, the MANIAC obtained the first equation of state calculated by modified Monte Carlo integration over configuration space.[7]

In 1956, MANIAC I became the first computer to defeat a human being in a chess-like game. The chess variant, called Los Alamos chess, was developed for a 6×6 chessboard (no bishops) due to the limited amount of memory and computing power of the machine.[8]

The MANIAC ran successfully in March 1952[9][10][11] and was shut down on July 15, 1958.[12] However, it was[13][14] transferred to the University of New Mexico in bad condition, and was restored to full operation by Dale Sparks, PhD. It was featured in at least two UNM Maniac programming dissertations from 1963.[15] It remained in operation until it was retired in 1965. It was succeeded by MANIAC II in 1957.

A third version MANIAC III was built at the Institute for Computer Research at the University of Chicago in 1964.

Notable MANIAC programmers

- Mary Tsingou – developed algorithm used in the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem

- Klara Dan von Neumann – wrote the first programs for MANIAC I[16]

- Dana Scott – programmed the MANIAC to enumerate all solutions to a pentomino puzzle by backtracking in 1958.[17]

- Marjorie Devaney – one of the first MANIAC I programmers.[18]

- Arianna W. Rosenbluth – wrote the first full implementation of the widely used Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm.

- Paul Stein and Mark Wells – implemented Los Alamos chess.[19]

Gallery

-

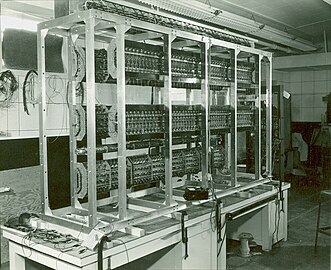

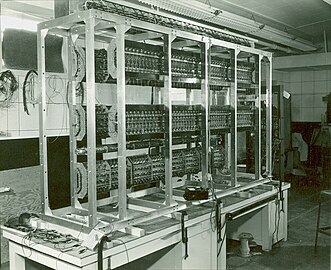

The MANIAC's chassis under construction in 1950.

The MANIAC's chassis under construction in 1950. -

MANIAC project leader Nicholas Metropolis (standing) and the MANIAC's chief engineer Jim Richardson in 1953.

MANIAC project leader Nicholas Metropolis (standing) and the MANIAC's chief engineer Jim Richardson in 1953. -

Marjory Jones (Devaney), a mathematician and programmer, is shown here in 1952, punching a program onto paper tape to be loaded into the MANIAC.

Marjory Jones (Devaney), a mathematician and programmer, is shown here in 1952, punching a program onto paper tape to be loaded into the MANIAC. -

Operators are pictured here in 1952 in front of the MANIAC. The horseshoe on the pillar on the right was hung for luck.

Operators are pictured here in 1952 in front of the MANIAC. The horseshoe on the pillar on the right was hung for luck. -

Paul Stein and Nicholas Metropolis play Los Alamos chess against the MANIAC, a simplified version of the game without bishops. The computer still needed about 20 minutes between moves.

Paul Stein and Nicholas Metropolis play Los Alamos chess against the MANIAC, a simplified version of the game without bishops. The computer still needed about 20 minutes between moves.

See also

References

- ^ Pang, Tao (1997). An Introduction to Computational Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48143-0. OCLC 318210008.

- ^ Wennrich, Peter (1984). Anglo-American and German Abbreviations in Data Processing. De Gruyter. p. 362. ISBN 9783598205248.

MANIAC Mathematical Analyzer, Numerical Integrator and Computer

MANIAC Mechanical and Numerical Integrator and Calculator

MANIAC Mechanical and Numerical Integrator and Computer - ^ Metropolis 1980

- ^ "Daybreak of the Digital Age". Princeton Alumni Weekly. Published in the April 4, 2012 Issue. 2016-01-21. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

MANIAC was a single 6-foot-high, 8-foot-long unit weighing 1,000 pounds.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Computing and the Manhattan Project". Atomic Heritage Foundation. July 18, 2014. It's a MANIAC.

MANIAC was substantively smaller than ENIAC: only six feet high, eight feet wide, and weighing in at half a ton.

1 short ton (2,000 lb) - ^ Declassified AEC report RR00523

- ^ Equation of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines. Journal of Chemical Physics 1953

- ^ Pritchard (2007), p. 112

- ^ See Computing & Computers: Weapons Simulation Leads to the Computer Era, p. 135

- ^ Berry, Kenneth J.; Johnston, Janis E.; Mielke, Paul W. Jr. (2014-04-11). A Chronicle of Permutation Statistical Methods: 1920–2000, and Beyond. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109. ISBN 9783319027449.

- ^ Computing at LASL in the 1940s and 1950s. Department of Energy. 1978. p. 16.

- ^ Turing's Cathedral, by George Dyson, 2012, p. 315

- ^ Computing at LASL in the 1940s and 1950s. Department of Energy. 1978. p. 21.

- ^ "Oral-History:Marjorie 'Marge' Devaney". Engineering and Technology History Wiki. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ "Electrical and Computer Engineering ETDs". The University of New Mexico Digital Repository. UNM. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Kelly, Kevin (17 February 2012). "Q&A: Hacker Historian George Dyson Sits Down With Wired's Kevin Kelly". WIRED. Vol. 20, no. 3. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ Golomb, Solomon (1994). Polyominoes (second ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-691-02444-8.

- ^ "Oral-History:Marjorie 'Marge' Devaney". Engineering and Technology History Wiki. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Pritchard (1994), p. 175

- Brewster, Mike. John von Neumann: MANIAC's Father (archived) in BusinessWeek Online, April 8, 2004.

- Harlow, Francis H. and N. Metropolis. Computing & Computers: Weapons Simulation Leads to the Computer Era, including photos of MANIAC I

- N. Metropolis and J. Worlton (January 1980), "A Trilogy on Errors in the History of Computing", Annals of the History of Computing, 2 (1): 49–55, doi:10.1109/mahc.1980.10007, OSTI 4628499, S2CID 9201972

- "MANIAC documentation" (PDF). www.bitsavers.org.

- Metropolis, Nicholas; Rosenbluth, Arianna W.; Rosenbluth, Marshall N.; Teller, Augusta H.; Teller, Edward (1953), "Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines", The Journal of Chemical Physics, 21 (6): 1087–1092, Bibcode:1953JChPh..21.1087M, doi:10.1063/1.1699114, OSTI 4390578, S2CID 1046577

- Pritchard, D. B. (2007). "Los Alamos Chess". In Beasley, John (ed.). The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants. John Beasley. ISBN 978-0-9555168-0-1.

External links

- Photos:

- "Los Alamos MANIAC computer - CHM Revolution". www.computerhistory.org.

- "Los Alamos Lab on Twitter". Twitter.

- "Index of /resources/still-image/MANIAC/". archive.computerhistory.org.

- v

- t

- e

- SILLIAC (1956)

- WEIZAC (1955)

- SARA (1957)

- SMIL (1956)

- EDB-1 (1957)

- TRASK (1964)

| See also |

|

|---|---|

| IAS family |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Illinois |

| ||||

| Harvard University |

| ||||

| IBM |

| ||||

| University of Pennsylvania |

| ||||

| EMCC | |||||

| Sperry Rand Corporation |

| ||||

| Raytheon |

| ||||

| See also | |||||

- Colossus computer (1943)

- Transistor computer

- Vacuum-tube computer

- History of computing hardware

- History of computing hardware (1960s–present)

- List of pioneers in computer science